What is the working principle of an inductor?

What is the Working Principle of an Inductor?

I. Introduction

Inductors are fundamental components in electrical circuits, playing a crucial role in the behavior of alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) systems. An inductor is a passive electrical device that stores energy in a magnetic field when electric current flows through it. This ability to store energy and influence current flow makes inductors essential in various applications, from power supplies to radio frequency (RF) circuits. In this blog post, we will explore the working principle of inductors, their behavior in circuits, types, applications, and their significance in electrical engineering.

II. Basic Concepts

A. Definition of Inductance

Inductance is the property of an inductor that quantifies its ability to store energy in a magnetic field. It is measured in henries (H) and is defined as the ratio of the induced electromotive force (EMF) to the rate of change of current. The higher the inductance, the more energy the inductor can store.

B. The Role of Magnetic Fields in Inductors

When current flows through a conductor, it generates a magnetic field around it. In an inductor, this magnetic field is concentrated and can store energy. The strength of the magnetic field is proportional to the amount of current flowing through the inductor and the number of turns in the coil.

C. Key Parameters of Inductors

1. **Inductance (L)**: The measure of an inductor's ability to store energy, expressed in henries (H).

2. **Current (I)**: The flow of electric charge through the inductor, measured in amperes (A).

3. **Voltage (V)**: The electrical potential difference across the inductor, measured in volts (V).

4. **Time (t)**: The duration over which the current changes, measured in seconds (s).

III. The Working Principle of an Inductor

A. Faraday's Law of Electromagnetic Induction

Faraday's Law states that a change in magnetic flux through a circuit induces an electromotive force (EMF) in that circuit. This principle is fundamental to the operation of inductors. When the current flowing through an inductor changes, the magnetic field around it also changes, leading to the induction of an EMF that opposes the change in current. This phenomenon is known as self-induction.

1. Explanation of the Law

Faraday's Law can be mathematically expressed as:

\[ \text{EMF} = -L \frac{dI}{dt} \]

where \( L \) is the inductance, \( \frac{dI}{dt} \) is the rate of change of current, and the negative sign indicates that the induced EMF opposes the change in current (Lenz's Law).

2. Application to Inductors

In practical terms, when the current through an inductor increases, the inductor generates an opposing voltage that resists this increase. Conversely, when the current decreases, the inductor generates a voltage that tries to maintain the current flow. This behavior is crucial in smoothing out current fluctuations in circuits.

B. Self-Induction

1. Definition and Explanation

Self-induction is the phenomenon where a changing current in an inductor induces an EMF in the same inductor. This induced EMF acts to oppose the change in current, leading to a delay in the current's rise or fall.

2. Induced Electromotive Force (EMF)

The induced EMF can be calculated using Faraday's Law. For example, if the current through an inductor changes rapidly, the induced EMF will be significant, leading to a noticeable delay in the current's response.

C. Mutual Induction

1. Definition and Explanation

Mutual induction occurs when a changing current in one inductor induces an EMF in a nearby inductor. This principle is the basis for transformers, where two inductors are magnetically coupled.

2. Coupling Between Inductors

The degree of coupling between inductors is characterized by the mutual inductance, which depends on the physical arrangement and the magnetic properties of the materials involved. High mutual inductance allows for efficient energy transfer between inductors.

IV. Inductor Behavior in Circuits

A. Inductor in Direct Current (DC) Circuits

1. Initial Response to Current

In a DC circuit, when a voltage is applied to an inductor, the current does not immediately reach its maximum value. Instead, it gradually increases due to the inductor's opposition to the change in current. The time it takes for the current to reach approximately 63% of its maximum value is known as the time constant (\( \tau \)), which is given by:

\[ \tau = \frac{L}{R} \]

where \( R \) is the resistance in the circuit.

2. Steady-State Behavior

Once the current reaches a steady state, the inductor behaves like a short circuit, allowing current to flow freely without opposition. At this point, the magnetic field is fully established, and the inductor no longer induces an EMF.

B. Inductor in Alternating Current (AC) Circuits

1. Reactance and Impedance

In AC circuits, the current and voltage are constantly changing. The inductor's opposition to this change is characterized by its reactance (\( X_L \)), which is given by:

\[ X_L = 2\pi f L \]

where \( f \) is the frequency of the AC signal. The total impedance (\( Z \)) of an inductor in an AC circuit is a combination of resistance and reactance.

2. Phase Relationship Between Voltage and Current

In an AC circuit, the voltage across an inductor leads the current by 90 degrees. This phase difference is crucial in applications such as tuning circuits and filters, where the timing of voltage and current is essential for proper operation.

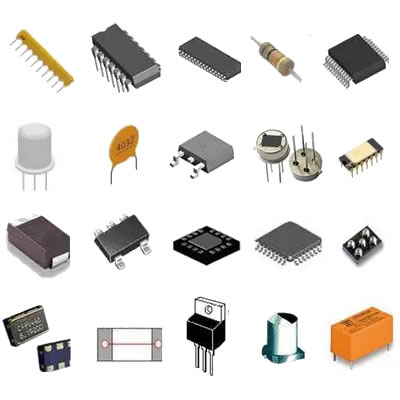

V. Types of Inductors

Inductors come in various types, each suited for specific applications:

A. Air-Core Inductors

These inductors use air as the core material, making them lightweight and suitable for high-frequency applications. They have lower inductance values compared to other types.

B. Iron-Core Inductors

Iron-core inductors use iron as the core material, which increases inductance due to the higher magnetic permeability of iron. They are commonly used in power applications.

C. Ferrite-Core Inductors

Ferrite-core inductors use ferrite materials, which are effective at high frequencies and are often used in RF applications. They provide high inductance in a compact form.

D. Variable Inductors

Variable inductors allow for adjustable inductance, making them useful in tuning circuits and applications where precise control of inductance is required.

E. Specialty Inductors (e.g., Toroidal Inductors)

Toroidal inductors have a doughnut-shaped core, which minimizes electromagnetic interference and is often used in power supplies and audio applications.

VI. Applications of Inductors

Inductors are used in a wide range of applications, including:

A. Energy Storage in Power Supplies

Inductors store energy in their magnetic fields, making them essential in switching power supplies and energy storage systems.

B. Filtering in Signal Processing

Inductors are used in filters to block unwanted frequencies while allowing desired signals to pass, crucial in audio and communication systems.

C. Transformers and Coupling Applications

Inductors are fundamental components in transformers, enabling voltage conversion and energy transfer between circuits.

D. Inductors in Radio Frequency (RF) Applications

Inductors are used in RF circuits for tuning and impedance matching, ensuring efficient signal transmission and reception.

VII. Conclusion

Understanding the working principle of inductors is essential for anyone involved in electrical engineering or electronics. Their ability to store energy, influence current flow, and interact with magnetic fields makes them invaluable in a wide range of applications. As technology advances, the development of new inductor materials and designs will continue to enhance their performance and expand their applications.

VIII. References

For further study on inductors and electromagnetic theory, consider the following resources:

1. "Electromagnetic Fields and Waves" by Paul Lorrain and Dale Corson

2. "Electrical Engineering: Principles and Applications" by Allan R. Hambley

3. Online resources such as educational websites and video lectures on electrical engineering topics.

By exploring these materials, readers can deepen their understanding of inductors and their critical role in modern electrical systems.